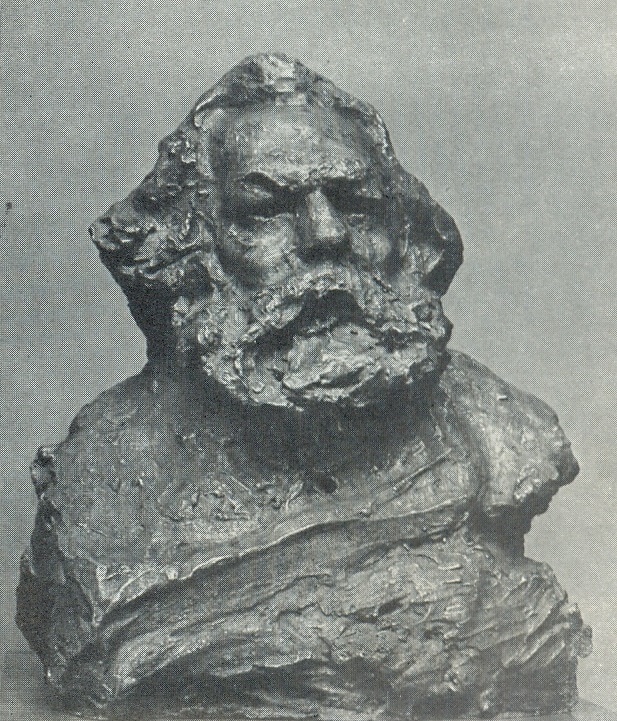

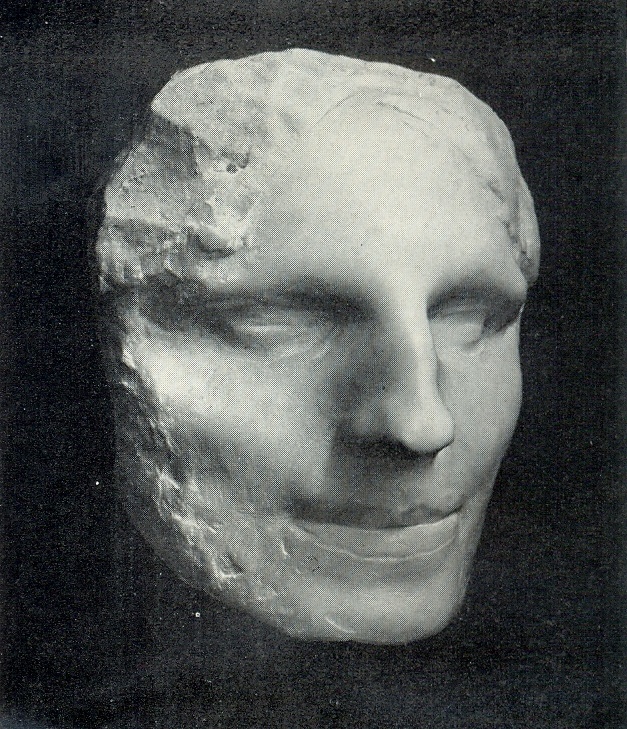

Soviet Russian sculptor Anna Golubkina 1864-1927

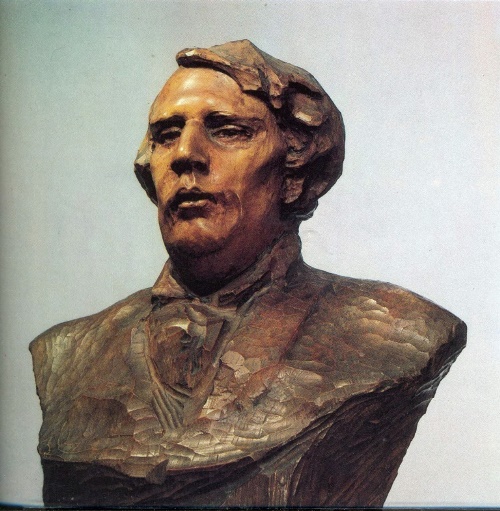

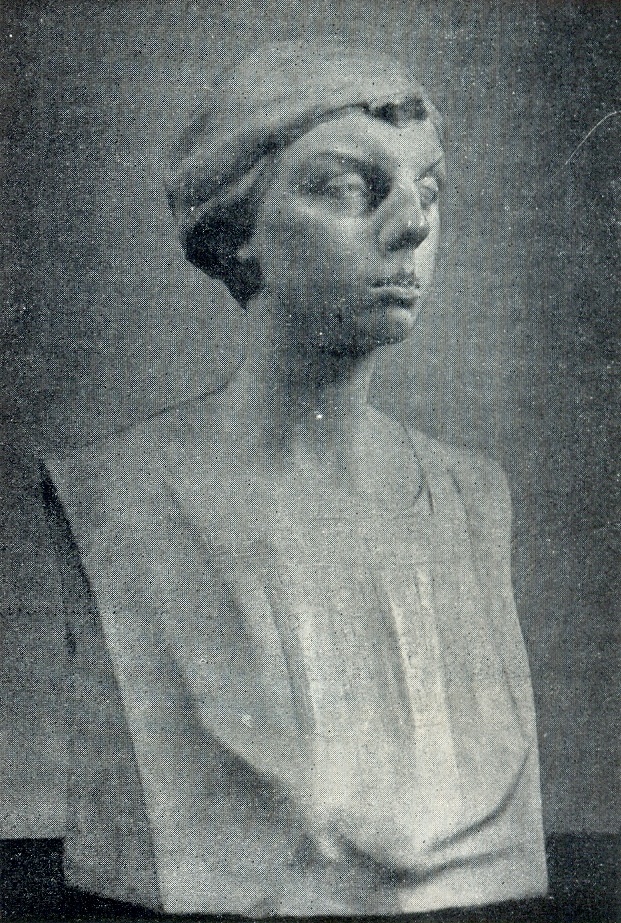

Soviet Russian sculptor Anna Golubkina – the largest sculptor of the late XIX – early XX century. The creativity of this genuine representative of the revolutionary-minded Russian intelligentsia served the noble cause of liberating the people from tsarist oppression. An outstanding master of portrait, she also created a number of remarkable works on social, revolutionary and philosophical themes.

The art of Anna Semyonovna Golubkina did not leave anyone indifferent. Her creativity developed at the turn of two centuries, two historical eras. Anna Semenovna Golubkina was born on January 28, 1864 in the provincial town of Zaraisk, Ryazan province. The granddaughter of the fortress peasant of the princes Golitsyn, she lost her father early, and had no opportunity to study at school. However, the natural mind and the tremendous thirst for knowledge allowed her to eventually become an educated person.

The environment in which Golubkina grew, Russian folk songs, legends and fairy tales heard in her childhood, the beauty of the surrounding nature had an impact on the formation of the world outlook and soul of the artist. Throughout her life, it fueled her creative imagination and served as a source of live impressions.

Up to twenty-five years Golubkina lived in her native city with a family engaged in gardening. Only in 1889 she came to Moscow, driven by a modest desire to learn how to paint pottery and earthenware. For some time the future sculptor studied at the workshop of artist-architect A.O. Gunst, and then, in 1891-1894, at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, workshops of sculptors SI Ivanov and S.M. Volnukhin. The enormous talent, purposefulness and striking ability of Golubkina allowed her in an extremely short time not only to acquire the necessary professional knowledge, but also to show her vivid individuality.

In 1894, without graduating from college, Golubkina entered the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts, the studio of VA Beklemishev. But in a year, unsatisfied and disappointed, she left for Paris. The official line in art, held at the Imperial Academy of Arts, cold and stiff, far from real life, did not meet the searches of an original sculptor. Golubkina wrote about this bitterly later, in 1907, to a famous French sculptor Auguste Rodin: “Before you, all the professors, except one Moscow sculptor Ivanov, told me that I am on the false path. And I can not work like I do. Their reproaches tormented me, but they could not correct me because I did not believe them. When I saw your work in the museum of Luxembourg, I thought to myself: “If this artist tells me the same thing, I must obey.”

Unfortunately, the first trip to Paris was unsuccessful. A half-starved existence, a selfless work in the private academy of F. Kolarossi, to which Golubkina devoted most of the day to her strength. The patient, with nervous exhaustion, friends soon brought her to Moscow. A two-year stay together with her sister in Siberia strengthened Golubkina’s health and simultaneously expanded her understanding of the life of the people in tsarist Russia.

In the complex process of the social changes that were taking place at that time, Golubkina saw the main thing-the formation of the Russian working class. Returning to Moscow, she created in 1897 the first in the domestic plastic image of the worker. As if foreseeing the future – an uneasy path of struggle, defeats and victories of the new class of Russia, – the author will give the name to the sculpture “Zhelezny” (1897). Thus, Golubkina opened the main theme, dedicated to the Russian proletariat.

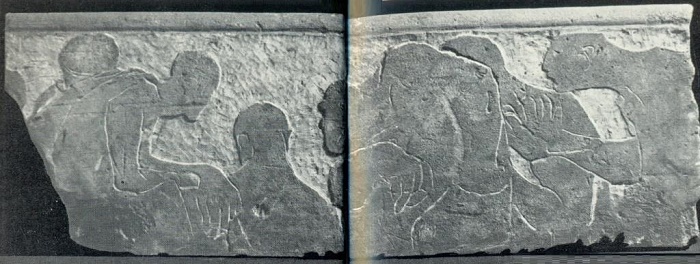

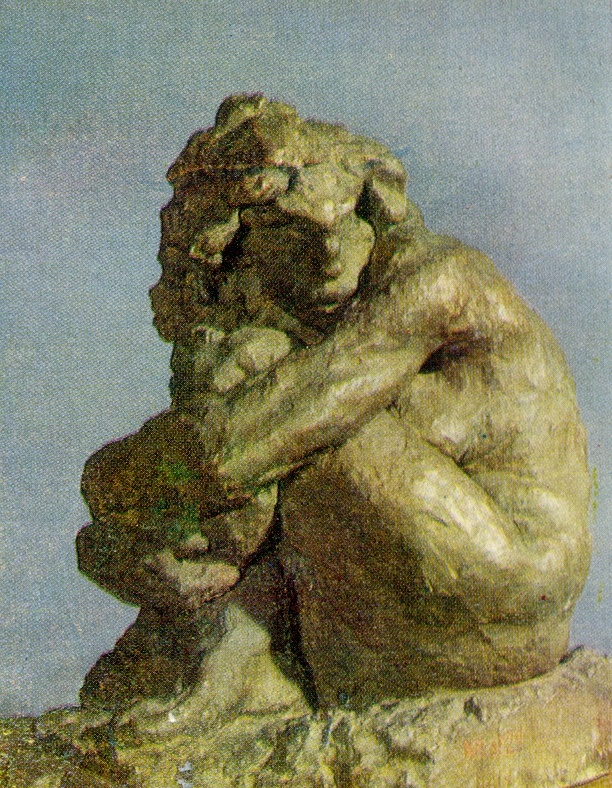

At the end of 1897 the sculptor left for Paris for the second time and stayed there until the fall of 1899. It was the time, when Golubkina met with O. Rodin. Although she was not a student of Rodin, she was able to use his advice. With the greatest respect of Golubkina to Roden, she did not become his follower, retaining the identity and features of a deeply national artist. Meanwhile, in Paris, Golubkina modeled the naked figure “Old Age”, using the model of the great master, the old Italian, who posed for Roden for the famous statuette “Belle Omier” (1885), now stored in the Luxembourg Museum. With this work, exhibited in the spring of 1899 in Paris, the sculptor declared herself an independent mature artist of a philosophical mindset, prone to acute psychological subjects, perfectly mastering professional skills.

Seeking to learn how to work on marble, in 1902, for the third time, Golubkina went to Paris, where she mastered this remarkable skill in perfection. On the return to Moscow, in 1903, her hard, full of asceticism life began, marked by successes and disappointments, life given to art. This is exactly the way Golubkin imagined the thorny path of the sculptor.

But becoming an artist, Golubkina did not limit herself with professional interests. The materials discovered in recent years reveal completely unknown pages of the biography of the sculptor. In particular, such aspects of her life that she hid even from her closest friends. Golubkina was directly connected with the Moscow Committee of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party and took an active part in revolutionary work. In life and in art, she was a convinced fighter against tsarism, for social justice. Moreover, the illegal literature seized from Golubkina during the search led to the arrest in 1907.

As the democratic moods of the artist acquired a revolutionary coloring and then specific forms of social and revolutionary activity, soon there were images of Russian proletarians, farm laborers and ordinary women. These were the people, whose images had never before been so vividly and multifaceted in sculpture. The prototypes of many widely known works of Golubkina were residents of the native Zaraysk and the surrounding villages. On the great truth of the soul of Golubkina, her pure, boundless love for man.

Soviet Russian sculptor Anna Golubkina

Source – Illustrated album. Author KV Ardentev “Anna Golubkina.” Publishing house “Fine Arts”, Moscow, 1976