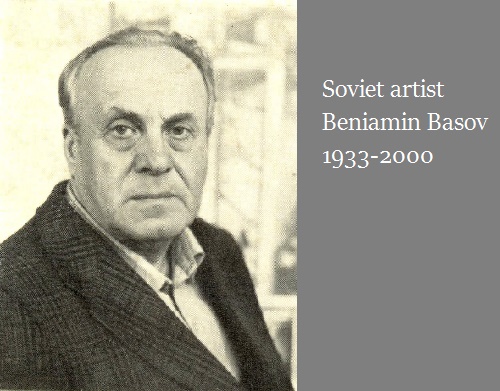

Soviet artist Beniamin Basov 1933-2000

Soviet artist Beniamin Basov

The bright, changeable, sometimes full of contrasts the life of the Soviet art has left its mark on the creative biography of the vast majority of artists who started their way into the post-war years. Considering many of them, you see how changed the language of art over the years, finding new forms, and new themes.

Beniamin Basov seemed to stand apart from these rather drastic changes. Since that time, he graduated from the Moscow Art Institute (1948), and his work developed by its own laws, while maintaining amazing consistency and integrity. Having received from his teachers (primarily from Sergei Vasilyevich Gerasimov) traditions of Russian realistic art, Basov stays true to this tradition. His paintings and drawings always maintain the vitality of the observations, the accuracy of the figure, and the objectivity of artistic vision. These qualities are inherent in the art of Basov constantly – from the mid-fifties to his last day.

You can distinguish his works at a glance – simple, low-key, and extremely reliable. For years – the same themes, motifs in paintings and drawings, and the same understanding of the writer, clearly perceptible in the illustrations. The artist again and again returns to the found compositions, rewrites many times the same canvas, working on it for several years, leaving it and returning to it again.

Circle of interests of Basov is very constant: to illustrate the works of Dostoevsky and Chekhov, the work on the scenery in and around Moscow – paintings and graphic. For nearly a decade he worked on the series of paintings to literature about the Great Patriotic War. In fact, these four “areas” or “line” almost run out of creativity of Basov. Beyond them is made a little, mainly in the fifties, when the artist had to execute a variety of books. Some of them (like “Earl Mont Cristo” by Alexandre Dumas) can be considered clearly extraneous to Basov, other works of the fifties – the illustrations for “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” by Tolstoy, and “The last days of Pushkin” by I. Andronikov – can be considered as a kind of preparatory for further stage.

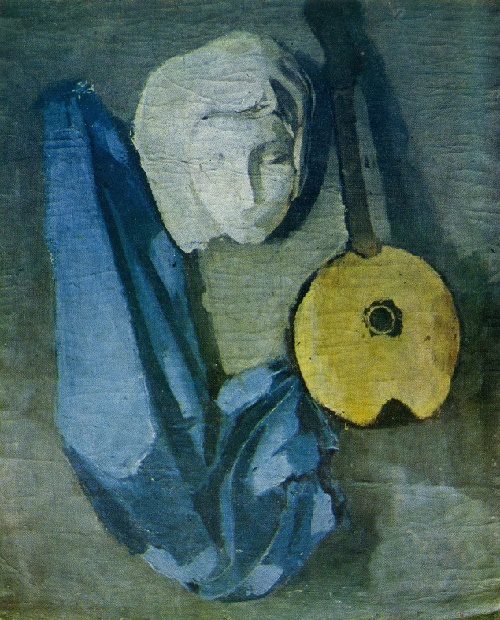

As a person and artist Beniamin Matveyevich Basov formed unusually early, and began his career – unusually late. Considering the few remaining early works, such as “Still Life with a mask” (1934), one can only wonder how a twenty-year boy, who grew up in a provincial Belarusian town, in an environment that did not have a clue about art, and without having seen a single original picture, and, in fact, no school (three-year art school in Vitebsk could give very little), – how he managed with such force, with such professional skill and confidence realize all his complex and multi-valued images, and assert his distinct artistic principles.

Basov revealed himself as an artist only in the second half of the fifties, a mature 40-year-old man, due to many external circumstances. Among them – work in publishing, then service in the army, impossibility to enter art college until 1938. Besides, the war years stretched training period at the institute for a whole decade. In addition, a difficult art post-war period led to the fact that he became known only in his forties. The shown in the 1961 exhibition works impressed everyone with their maturity, principles of belief, and consistent realism.

It seems that none of the artistic concept does not carry so many contradictions and ambiguities as a friendly term “realism.” For a hundred years the word denotes very different art: a broad generalization and transfer of petty details; thinnest shaped psychology and photographic likeness; a deep understanding of the world and a passive “surface layer” of life; formidable naked truth and a lie, made-up under the external credibility. For deep and talented artists and researchers, the term always sounded in the first place, as the definition of the internal content of art, understood as “the reality of human emotions,” and as “the real truth of life.”

Basov was one of those who carried through his creativity a real sense of life, its unvarnished truth – something that has always been and remains the best quality of Russian and Soviet art. Intense drama creativity of Basov sounded in the works of the 40-50-ies in full force, although the most significant, especially in graphics, was made later, in the sixties and seventies.

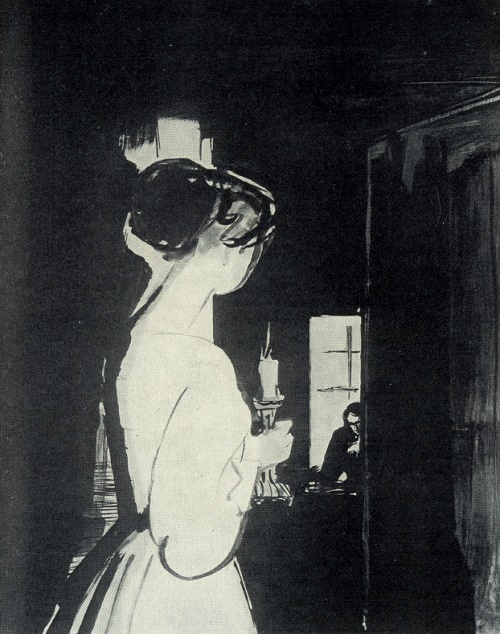

Bent over the dying girl sad young man in the picture to the libretto of the opera D. Puccini’s “La Boheme” (1958); exhausted, helpless, pinned to the impending darkness Ivan Ilyich in the illustrations for “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” by L. Tolstoy (1957); sad, confused, in their heavy thoughts Chekhov’s Three Sisters (1958); wounded Pushkin, carefully maintained by Dantes, to the cover of the book of I. Andronikov – all these profoundly human images were full of warm sympathy of the artist, his “empathy” with heroes. And a sharp contrast of black and white created and stressed this feeling.

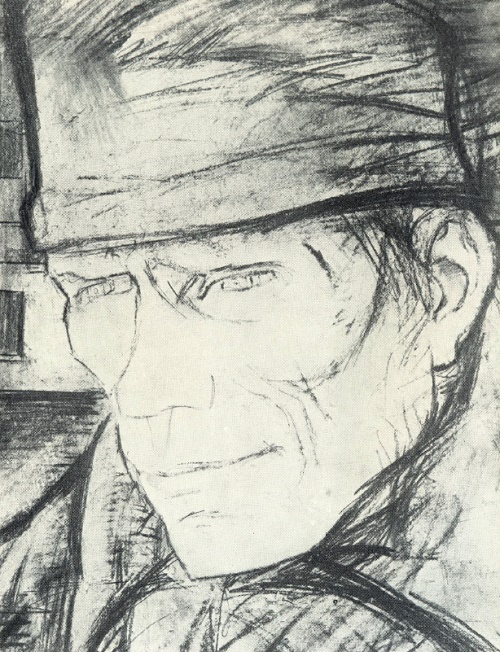

Military drawings of Basov became deeply dramatic story about a man in a displaced, terrible world war. The first five illustrations to the “Fate of a Man” was made (in 1965). They were executed for the International Book Exhibition in Leipzig. Then, in 1967, six large compositions have been completed, and received the general name of “Soviet literature of World War II.” Immediately after the cycle of military drawings followed illustrations of the works of Dostoevsky – a large series of drawings to the “Poor people” was completed in 1970. Shown at the International book exhibition in Leipzig in 1971, among other Soviet illustrations, it won the gold medal.

Endless human loneliness, lostness, and emptiness among the thousands of people in a large city was the main content of Basov drawings to the “Poor people” and even more so – to the drawings “White night”.

Drawings of Basov cause complicated move of Audience associations. In this respect, they are not inferior to the contemporary illustrations, which are called “associative”, – illustrations, where “the artist sees the world with his own eyes, says that excites him in this world, as a starting point of reflection – a literary work.”

Basov – master of dramatic, intense, often tragic genre. He sees life, past and present, in all its contradictory complexity. He feels hidden power and movement, exposes them, penetrating with glance the quiet everyday human existence. He knows that the fate of each, every life, small and inconspicuous on the outside look, hides a feeling of passion, and tragedy of truly Shakespearean proportions. The dramatic nature of Basov works originates in the greatest attention to the people, and a deep respect for each destiny, to every human feeling.

The artist sharply rejects the indifference, disregard for the people, and all that can play down, neutralize human. Basov Art – is primarily a statement of man as a person, a passionate appeal to the man – be a person. The artist knows that the real forms of life often hide a greater acuity than creative imagination can. We only need to see and convey what life brings. And Basov has such a talent.

Soviet artist Beniamin Basov

A. Dumas. The Count of Monte Cristo. Cover. 1955

Death of Ivan Ilyich (L.N. Tolstoy). 1956

Evening window. 1954

Evening. 1962

Houses lit with the sun. 1950

Ilya. 1944

Khotkovo. 1957

Landscape with kiosk. 1960

Landscape with sun. 1963

Lorry at the river. 1960

On Chekhov motifs. 1958

Platform on a Savyolovo railway road. 1957

Portrait of wife. 1962

Rainy evening. 1960

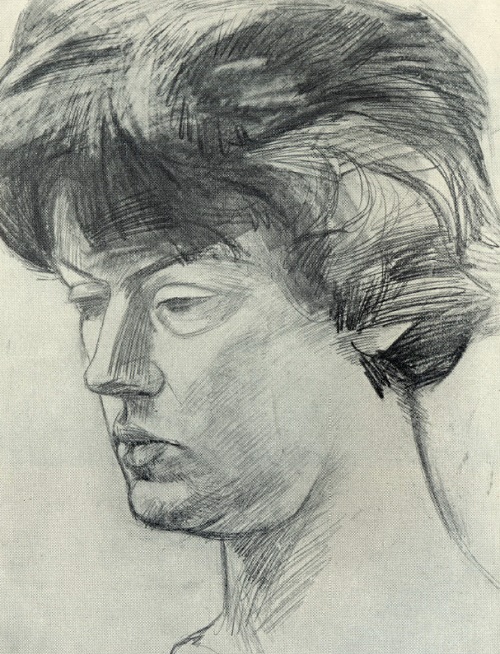

Student. 1942

The village of Grigorovo. 1959

The village of Porechie. 1963

Three sisters (A. Chekhov). 1957

Three years. On stories by A. Chekhov. 1958

Two trees. 1959

White nights (Fyodor Dostoevsky). 1958

A girl on the balcony. 1964

A. Tolstoy. Russian character. Illustration. 1967-1970

A. Tvardovsky. House at the road. Leaving for the front. 1967

Assizi. 1967

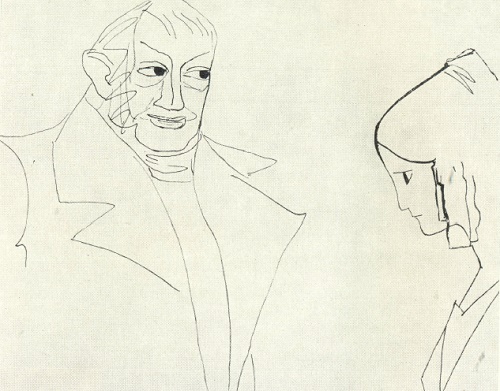

Balzac. Brilliance and poverty of courtesans. 1963

Barn. 1970

Brilliance and poverty of courtesans. 1963

Factory in Tuchkovo. 1960

Female portrait. 1969

Fences. 1964

Girl in profile. 1964

H. Balzac. Brilliance and poverty of courtesans. 1963

Honore de Balzac. Brilliance and poverty of courtesans. 1963

In the concentration camp. Illustration to ‘The destiny of man’ by Sholokhov. 1964

Landscape with a horse. 1968

Landscape with a meadow. 1963

Lane. 1962

Man’s head. 1964

Man’s head. 1965

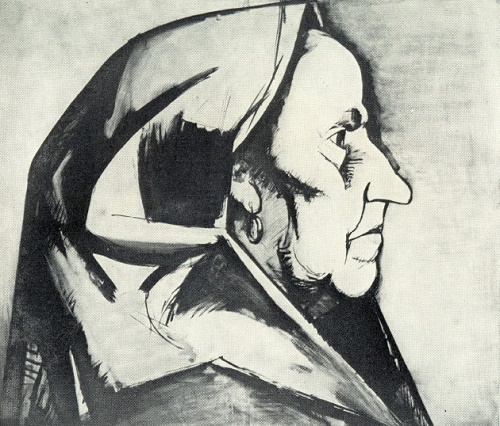

Old woman. ‘They fought for their country’ by Sholokhov. Illustration. 1967

On Chekhov motif. 1968

Portrait of I. Nabatov. 1962

Prisoners of war. Illustration to ‘The destiny of man’ by Sholokhov. 1964

Road. 1969

Sholokhov. The destiny of man. Farewell. Illustration. 1964

Station. 1964

Tuchkovo railway station. 1964

Village in rain. 1960

Yura. 1964

At the bridge. Drawing on Dostoevsky novel Poor people’. 1967-1971

Button. Illustration to Poor people by Dostoevsky

Devushkin on stairs. Illustration to Poor people

Fall. 1966

Funerals. Illustration to Poor people. 1967 – 1971

Gray day. 1966

Hot day. 1972

Makar Devushkin. Illustration to Poor people by Dostoevsky

Sunny evening. 1972

Village on a hill. 1970

Village. 1968

Ward No. 6. Illustration 1976-1979

source

Illustrated album ‘Beniamin Basov’. Soviet artist. 1980