Early Soviet film posters

Movie Posters have long been separate kind of art. Early Soviet film posters adorned the main theaters of the country and places of public festivals. The popularity of cinema in those years was so high that sometimes people had to stand in long queues to buy cherished tickets! Why the old Soviet movie posters were made as a picture and not as staged photography, photo collage or a film frame? The answer is obvious: because it was much cheaper. Digital Technologies of that time did not allow to publish millions of large size photo posters for all the theaters, cultural centers and other institutions of a giant country. It would be impossible and impractical. In addition, to make a big picture in large size and good resolution would be very problematic.

Movie posters were of two kinds: 1. printed illustration, 2) movie poster of different sizes – from one square meter to several tens of square meters, painted right on the facades of cinemas, fences, special pillars, so called “live” posters. Unfortunately, while nobody guessed to chronicle drawn gouache posters, they were not photographed, so the whole layer of our film history and film industry can be considered lost. Have survived only printed posters.

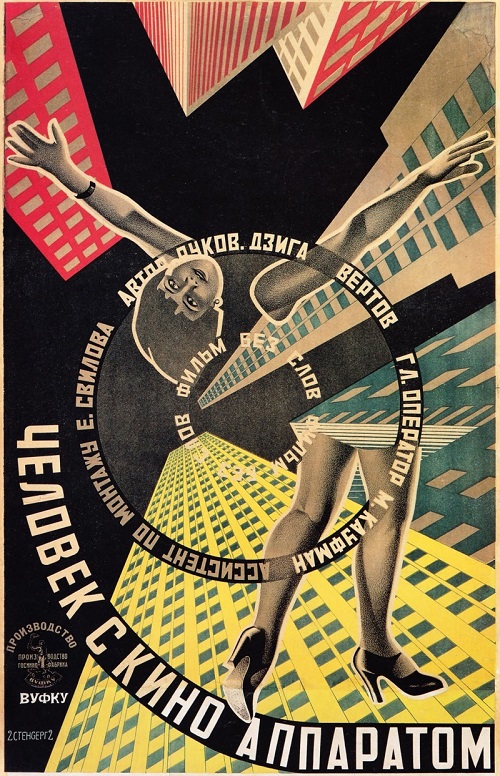

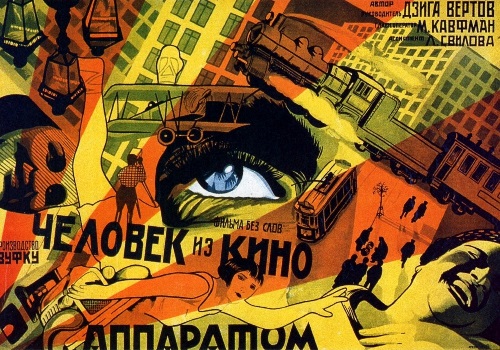

Man with a Movie Camera, 1929, the USSR. Vertov’s documentary, which shows the life of Soviet Russia of 1920s. It’s more like a sort of assorted shots of real life. This film consists of a plurality of scenes, each of which lasts less than 10 seconds. Here are shown the beautiful views of the capital, a variety of public places, where people are constantly present.

Man with a Movie Camera. In the frame of the movie camera shoots people, places, objects … Here the Movie Camera is protagonist of the shooting process: in the air, under the ground, in the thick of things … Cinema-eye that observes, captures every nuance, without giving estimates without following scenario. It just looks at the world and sees all, or rather, there is a vision!

Aelita, 1924, USSR. The first Soviet film in the genre of science fiction. As a literary basis was published shortly before an eponymous novel by Alexei Tolstoy that enjoyed popularity among readers. The story line (interplanetary expedition) gave an interesting and diverse material to create entertaining film.

It intertwined juicy everyday scenes of life in Moscow in the first years of the New Economic Policy with fantastic scenes – the flight to Mars, the meeting of “earthly” engineer with ruler of Mars Aelita, attempt to revolt, “the proletarian of Martians” against their oppressors and defeat. The novel ended with safe return of interplanetary expedition to Earth. The film was not accepted any criticism, any spectator.

Early Soviet film posters

Early 1930-ies. Far East. In the center of the film – Siberians who fight against Samurai saboteurs, trying to disrupt the construction of an outpost of the Soviet Union’s eastern borders. Movie Title “Aerograd” – name of the city that is not on the map. Aerograd – the fruit of a dream, a fantasy of the great social cinema-poet. The world of the film is split into two conflicting spheres. New and old. Good and evil. Friends and enemies. Light and darkness.

director Alexander Dovzhenko.

Based on the novel by AS Pushkin.

Peasant revolt, pictures of righteous anger – that’s the focus that has been put into a film by Alexander Ivanovsky. The manuscript of the novel was found after Pushkin’s death in his papers. The novel had no title, and remained unfinished. The idea of “Dubrovsky” was prompted by the actual incident. Ivanovsky acquainted with the novel and wrote its end: the rebellious peasants killed despot Troyekurov.